UW-Whitewater history professor awarded national Whiting fellowship

May 20, 2021

Written and photos by Craig Schreiner

James Levy, an associate professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, has been awarded one of seven national 2021-22 Whiting Public Engagement Foundation fellowships with $50,000 to launch a new project, “Whose Land? Race, Settlement and Dispossession in Wisconsin and New York,” a new phase of the Wisconsin Farms Oral History Project that created the award-winning 2019 exhibition, “The Lands We Share.”

The “Lands We Share” effort, which Levy led — receiving a Whiting Public Engagement Seed Grant for $5,000 in 2018-19 — was a complex, multi-campus project including four University of Wisconsin campuses: Madison, Milwaukee, Oshkosh and Whitewater. Over the course of five years, the project team and students from each of those campus locations collected hundreds of interviews throughout the state regarding Wisconsin’s rich agricultural history and statewide cross-cultural connections to land and farming.

“The (WPEF) judges were deeply impressed with the project team's plan to expand on the remarkable success of the ‘Lands We Share’ initiative,” said Daniel Reid, executive director of WPEF. Reid said Levy excels at connecting people with scholarly work both during and after a project.

James Levy, left, confers in Laurentide Hall on the UW-Whitewater campus with Ken Virden, a public relations major from Marshall, about the “Lands We Share” project.

In “The Lands We Share” project, Levy sent student researchers into communities where they learned to build trust with those they interviewed and collaborated to share stories of farming, food, land and culture. The product was a traveling exhibition on farming, food, race and history, which served to frame farm-to-table dinners and conversations in each community along the tour. The exhibit’s stories, photographs, artifacts, audio interviews and conversations directly reached thousands of residents statewide and more than 100,000 people through Wisconsin Public Radio and social media.

“Engaging with the public means long-term and sustained collaborations, in addition to one-off projects and appearances,” said Levy. “Lectures, panels and student summer internships are really important too — crucial for community engagement. But long-term, frequent-contact partnerships are necessary to keep those community ties alive and agile — what’s necessary to allow scholars and students to engage in meaningful listening and to creatively and collaboratively envision meaningful work.”

McNair Scholar Jazmin Wilson, left, talks with James Levy, her mentor, about her undergraduate research project on urban farming.

Levy said the Whiting fellowship will allow the “Whose Land?” project to move forward with partners and campuses in upstate New York and New York City in addition to current Wisconsin partners, this time with a theme more directly focused on racial equity.

“In contrast to ‘Lands We Share,’ the ‘Whose Land?’ project will focus much more specifically on land dispossession, on histories of displacement (of peoples) and on land loss,” he said.

Levy said Wisconsin and New York share agricultural traditions, histories of white settler colonialism and interconnected histories of Abolitionism in the 19th century. The connection between the states begins with displacement as members of several Indigenous nations in New York moved — sometimes by force — to Wisconsin in the 1820s and 1830s. For example, members of the Oneida Nation now prominent in Wisconsin and a long-term “Lands We Share” partner were displaced from New York in the early 19th century. (In fact, both states have an Oneida County.) And black farming communities in 19th century rural Wisconsin were populated not just by migrants from the South but by families from eastern states including New York.

“Lands We Share” student intern Jennifer Young, left, a UW-Oshkosh student, interviews peer intern and Oneida Nation member Nick Metoxen at UW-Oshkosh in summer 2018. (Submitted photo/Max Cozzi)

“And the percentage of mostly white people from New York who settled here was phenomenal,” said Levy. “In 1850, one out of every two Wisconsinites was born in New York State.”

Levy foresees two teams of researchers in each state. The two Wisconsin teams will be assigned to urban topics in Milwaukee and rural topics in a large swath of the state from the northeast in the Fox Valley and southwest to the Driftless Area. The New York teams will be split between the rural Finger Lakes region in upstate New York and an urban team in Manhattan.

The University of Wisconsin campuses at Oshkosh, Madison, Milwaukee and Whitewater will collaborate again. The New York university partners so far are Cornell University, the State University of New York (SUNY) College of Environmental Science and Forestry’s Center for Native Peoples and the Environment at Syracuse, and Hunter College in Manhattan.

“There will be opportunities (for students) to work in Milwaukee and examine housing dynamics and urban narratives of displacement, opportunities to collaborate with Indigenous nations and with other farmers of color, and opportunities to engage with issues around migrant and seasonal labor. Anyone who is interested in history or in race will find interest in this project,” said Levy.

Levy, left, in the field interviewing Chia (center) and Cheu Vang, owners of Vang C & C Farms, on their land outside Jefferson, as part of the “Lands We Share” project. (Submitted photo/Max Cozzi)

“This is attractive for any student who wants to learn about field work,” added Levy.

“As traditional historians we are often taught how to work in an archive. I also want to teach students generally how to work outside in the field: how to go into churches and neighborhood centers, how to talk to families, how to cold-call community leaders.”

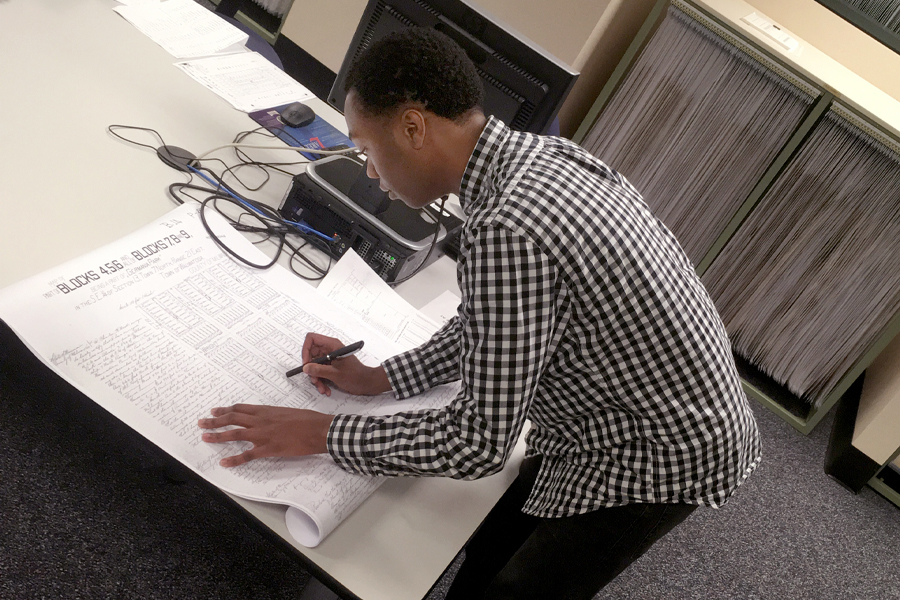

In the “Lands We Share” project a powerful thing actually did happen in an archive.

Levy was shoulder-to-shoulder with student Donovan Hemphill, a UW-Whitewater international journalism and psychology major from Milwaukee, in the Milwaukee Register of Deeds office. They were tracing the land genealogy of the Metcalfe Park Legacy Garden, a community garden reclaimed from vacant lots and empty houses. Levy and Hemphill wanted to know the last time that land was a farm.

As they worked, Levy looked up at one point and saw himself and Hemphill lost in dry government documents — yet both were smiling. They were onto something. Teacher and student immersed, at the same time, in a community.

Days before they had stood on the same parcel of land in Metcalfe Park now outlined on a surveyor’s map. As a child, Hemphill had lived two blocks from where they stood, a neighborhood where 44% of residents live below the poverty line. Now they were discovering the neighborhood’s story, historical layer by historical layer. Later Hemphill would take that story back to neighborhood leaders in Metcalfe Park and in that gesture win their trust in him and the project.

“In that moment, I knew something was working,” said Levy. “And I knew I wanted to keep experiencing as many moments like that as I could.”